If you arrived here from the plug for this blog graciously included by The Agony Booth in my new article on that site, welcome and enjoy your stay!

The Elusive World of Karel Zeman

When I was in seventh or eighth grade, I was devouring every movie book I could get my hands on. The Internet didn’t quite exist as a thing regular people were actually using, rather than merely hearing was going to be the next big thing. CD-ROMs were an awkward novelty that were still trying to figure out what their “interactive multimedia” was actually for, and I did not know of such proto-IMDb efforts as Microsoft’s Cinemania. When I stumbled on the rare laserdisc, I assumed it was an LP record.

Libraries still used card catalogs. I was able to find every movie-related book they had anyway.

And then I came across this review in one of Pauline Kael’s books:

The Fabulous World of Jules Verne

Czechoslovakia (1958): Fantasy

83 min, No rating, Black & White, Available on videocassette

Also known as VYNALEZ ZKAZY and DEADLY INVENTION.

Among Georges Méliès’ most popular creations was his 1902 version of Jules Verne’s A TRIP TO THE MOON (which was used at the beginning of Michael Todd’s production of AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS). Another great movie magician, the Czech Karel Zeman, also turning to Jules Verne for inspiration, made this wonderful giddy science fantasy. (It’s based on Facing the Flag and other works.) Like Méliès, Zeman employs almost every conceivable trick, combining live action, animation, puppets, and painted sets that are a triumph of sophisticated primitivism. The variety of tricks and superimpositions seems infinite; as soon as you have one effect figured out another image comes on to baffle you. For example, you see a drawing of half a dozen sailors in a boat on stormy seas; the sailors in their little striped outfits are foreshortened by what appears to be the hand of a primitive artist. Then the waves move, the boat rises on the water, and when it lands, the little sailors-who are live actors-walk off, still foreshortened. There are underwater scenes in which the fishes swimming about are as rigidly patterned as in a child’s drawing (yet they are also perfectly accurate drawings). There are more stripes, more patterns on the clothing, the decor, and on the image itself than a sane person can easily imagine. The film creates the atmosphere of the Jules Verne books which is associated in readers’ minds with the steel engravings by Bennet and Riou; it’s designed to look like this world-that-never-was come to life, and Zeman retains the antique, make-believe quality by the witty use of faint horizontal lines over some of the images. He sustains the Victorian tone, with its delight in the magic of science, that makes Verne seem so playfully archaic. Released in the U.S. with narration and dialogue in English.

Now, I was the sort of kid who had read every Jules Verne book I could find (with Facing the Flag definitely not among them). And who loved anything to do with special effects or creatures (even if I was confused by King Kong when I rented one of the only monster classics the local Blockbuster had in a colorized version. Why did it take so long to get to New York and why wasn’t Kong a truly detestable bad guy?) And yet, I could tell that the weird movie Kael was describing was something unique even in my wheelhouse.

Fast-forward to my college years. I had become vastly more knowledgeable, and sometimes even wise, about all aspects of film. Kim’s Video sure had a lot of the hard-to-find movies that I had read about in high school but weren’t at Blockbuster! I had started to get into artsy animation, renting pretty much everything Kim’s had, but was still mostly confined to American or Japanese stuff. And then my friend Niff introduced me to the new area of Czech animation, particularly the stop-motion animation with Rankin/Bass-style flexible-but-freestanding puppets by such luminaries as Jiri Trnka and Karel Zeman.

Eventually, I realized that the Karel Zeman who Niff was talking about was one and the same with the director of the oddball movie that Kael had so adored. Like Ray Harryhausen and George Pal, Zeman had transitioned from making shorts with puppets to full-length features with human actors, but the same special effects ingenuity and imagination they had done in their shorts. I finally was able to catch a screening of Zeman’s feature Baron Munchausen. But The Fantastic World of Jules Verne itself never showed up.

So, Kael’s review has stuck in my head for almost two decades, but I have never had a chance to see the intriguing movie described. Until now.

Thanks to a new restoration premiering at The Museum of the Moving Image, I have finally had the chance to see one of the most elusive gaps in my film history. Could it possibly live up to near-decades of expectations?

I’m overjoyed to be able to report that it does.

to be continued…

Yoda Stories, Episode V

It has been a year since my first (fourth?) incomplete foray into telling my personal Star Wars saga. So now it continues…

We pick up the story on a setting as barren as Hoth: pre-Internet high school. When nerd culture was as marginalized as, well, nerds were when the term was still an insult. When being a nerdy kid meant being as isolated as Harry Potter on Privet Drive. When science fiction having it better than fantasy (still fond of you, Willow) in a culture that was still optimistic about economic and technological prospects didn’t mean it was all that much better. When it was still possible to miss entire continents of what nerd culture was around at the time, such as assuming that Buffy the Vampire Slayer was another dopey Dawson’s Creek-ish teen show. When owning VHS tapes was a luxury, DVDs were nonexistent, and laserdiscs were assumed to be records.

After I’d seen the Star Wars trilogy, when it was still “the Star Wars trilogy”, Star Wars still loomed large. It didn’t really matter that there were just three movies; after all, E.T. was ubiquitous with just one. Sure, there were rumors of a planned “trilogy of trilogies”, but nobody was really sure about them. (Although we were sure that trilogies would come in threes.) I never really got into the Expanded Universe, but the existence of such ancillary material was enough to give Star Wars an ever-expanding feel. The radio dramas even expanded the scope of the trilogy’s stories themselves; not realizing that many of their scenes were not present in the movies, my memory mixed their fleshing-out the storyline in with my memories of the movies. Long before Disney’s official sequels, the expanded universe sequels and perennial sequel trilogy rumors gave the impression of an amorphously expandable universe that would continue the saga… sort of, eventually. (They might not have been “official canon” but that wasn’t really a big deal back then.)

The 1995 VHS release was a way to get ahold of the trilogy spiffed up with THX and Leonard Maltin. The “one last time” thing seemed like little more than Disney’s milking the latest VHS re-release with an imminent Disney Vaulting before the inevitable re-re-release. (Fitting that it fell to them to finally bring Star Wars out of the Lucasfilm Vault.) Without really believing they would displace the originals, and without the Internet to fuel (or even clue in) the more questionable aspects of the changes, the 1997 special editions were a way to see the movies in theaters with changes that were known about, but still assumed to be mostly about updating the production quality.

And as the new millennium loomed near, everything was on the verge of change…

(to be continued)

A decade of YouTube

Ten years ago today, the first YouTube video Me at the Zoo was posted.

It’s party time!

Comrade Jack Ross’s The Socialist Party of America: A Complete History, an 800-page tome offering a fresh perspective that’s in some ways a successor to the classic New Leftist take on the subject, James Weinstein’s The Decline of Socialism in America, 1912-1925, is out today in print and eBook editions. Join the fun!

Big Eyes: see the good movie Tim Burton made that nobody noticed

It’s out on video and DVD today. Tim Burton made a good movie! A really good movie! With people! People! Check it out.

Mad Men exhibit at Museum of the Moving Image: first impressions

This evening, the Museum of the Moving Image held a special members-only preview of the new exhibit “Matthew Weiner’s Mad Men” before it opens tomorrow. So here’s my unpolished impression of it.

Long before streaming made ephemeral film easy to see, the Museum was curating a full range of video obscurities. Even the clips from the show that can be viewed any time on Netflix or iTunes are a whole different experience in context, and there’s everything from a roll of clips from movies that sum up the Space Age aesthetic to a jukebox-like touchscreen of songs that influenced the show with commentary.

But while the exhibit covers the gamut of the show from scripts to characters, most of all, the extensive array of artifacts included ensures that the most forceful impact is the sheer sense of space and tangible time and place. With the multitudinous artifacts from the show, and even full-scale recreations of some of its environments, it conjures up the show’s trademark 1960s-before-The-Sixties as surely as an attic full of family photos, old vinyl collections, and National Geographic issues. In an era of computer graphics and ephemeralization, when all that is solid, even the iPod clickwheel, melts into bits, it conjures up a lost world of stuff. The focus on a meticulously created environment rather than plot is reminiscent of world-building efforts in science fiction and fantasy, including Jim Henson’s efforts in Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal. And it’s simply fortunate for those who aren’t as caught up as they would have liked (like, well, me). Even the museum’s previous Breaking Bad exhibit, far more plot-oriented by necessity for its subject, was understandable even to a viewer who had only seen the first season, and this one is similarly accessible.

Unless you absolutely can’t stand Mad Men for some reason (and why would you?), it’s worth a look.

M. Stanton Evans, RIP

The embodiment of the contradictions in the 20th century intellectual and strategic alliance of libertarianism with mainstream conservatism, Medford Stanton Evans, passed away earlier today at age 80. (Hat tip: Tennyson.)

He was a protégé of antiwar single-taxer Frank Chodorov who became a staunch defender of McCarthy — and we ain’t talkin’ about Gene.

I met him once, when he spoke at the Foundation for Economic Education a couple years back (at which time he seemed impossibly wizened, more Charles F. Muntz than Carl Fredricksen), and asked him about Chodorov. (He was also a student of Ludwig von Mises — not the Institute, the person — but even that firsthand contact through the gulf of time is less of a rarity.) Evans had warm personal memories of the man, and was appreciative that someone from my generation even knew who Chodorov was to ask about him. Needless to say, his answer avoided going into the tensions between Chodorov’s worldview and his own. And I can only imagine how appalled he would have been by my political views on other topics.

In his Q&A session, he did discuss Chodorov’s not-exactly McCarthyist take on McCarthyism — “The way to get rid of communists in government jobs is to abolish the jobs.” — which had impressed SDS’s Carl Oglesby (yes, that SDS) as a contrast to “the debased Republicanism” of the time. But Evans somehow seemed to think that this was only meant to apply to domestic government, and was thus entirely consistent with a Red-fighting foreign policy.

More generally, Evans was one of the originators of the broader mid-20th century revival of uncompromising conservatism centered around National Review. He was one of the main contributors to the “fusionist” redefining of libertarianism as coterminous with political and social conservatism. In fact, his talk repeatedly referred to the libertarian and conservative movements in the same breath.

Early movement conservatism had a surprisingly large contingent that hewed to Chodorov’s single tax views. William F. Buckley, Jr. would patiently explain his belief in single-tax views against private property in land whenever anyone bothered to ask. Ironically, that contingent never had a presence at FEE, even though Chodorov’s magazine The Freeman evolved into FEE’s flagship.

On top of that, conservatives occasionally simply veered in weird directions. For instance, Reagan staffer John McClaughry’s interest in “self-managed workplaces, neighborhood empowerment, alternative currencies, and decentralized technology” (Jesse Walker’s words); or Karl Hess’s, um, being Karl Hess. Hess might have left the conservative movement by the time he got really groovy, but he maintained that he was always driven by the same essential values. McClaughry was in the far odder position of giving a blurb, listing his then-current position of Senior Policy Advisor in the White House when Reagan was president, recommending that “Friends of cooperation, of self-sufficiency, of the household economy, of the small community, of sound money, and of a non-exploitative land tenure” read Mildred Loomis’ Alternative Americas — a book in which private interest and rent are opposed on Benjamin Tuckerite grounds. (Loomis was a protégé of Ralph Borsodi, another maverick individualist fighting singlehandedly against the early-20th century collectivist tide, though his influence from Paul Goodman to Robert Anton Wilson was in a different direction from Chodorov’s.) But as far as I am aware, Evans had no such funky side.

By the time Evans’ magnum opus defending McCarthy appeared in late 2007, it was so far out of sync with a libertarian movement weary of two terms of Republican crusading that its leading magazine, Reason, was scathing. The modern equivalent of National Review as the intellectual leadership in the conservative movement is the anti-bellicose The American Conservative, whose McCarthyist tributes are indeed to Gene and not Tail-Gunner Joe. The energy at FEE itself has long since shifted to a new generation with far more socially liberal cultural views, like Sarah Skwire and Steven Horwitz. The fading of Evans’ worldview long preceded him.

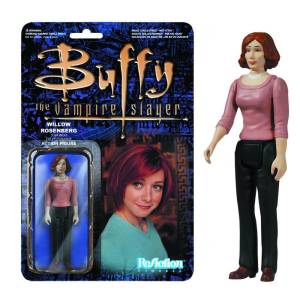

Willow Rosenberg: the LJN Nintendo sprite!

So, I stumbled on this ridiculously off-model action figure of Alyson Hannigan’s Willow Rosenberg from Buffy the Vampire Slayer:

The completely wrong hair and eye color, the expressionless face utterly lacking the charm of any photo of Hannigan, including the one right next to it on the box… I was baffled at first, but then I realized that it could only be an “I meant to do that” deliberate recreation of a bad 8-bit Nintendo sprite, just like ReAction’s figures for Jason and Freddy based on the infamous LJN games for the NES!

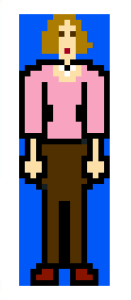

All the history books that tell us that NES games stopped being made three years before the show aired were obviously mistaken! But what exactly did this game’s version of Willow look like?

Exactly like this:

Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Markets, Free Press

Today I have the very first contributing editorial up at a brand-new outfit, the William Lloyd Garrison Center for Libertarian Advocacy Journalism. Fittingly, since its namesake was a journalist whose voice was dedicated to the abolitionist cause, I had the chance to respond to a very confusing take on abolitionism’s lessons for today. Founder (and until now sole contributor) Thomas L. Knapp is an old pro at writing, editing and submitting libertarian opinion to mainstream newspapers in a way that gets them to notice; he literally wrote the book on the subject. And now he has put his unique talents into his own entity devoted solely to the purpose. He has provided invaluable support for my writing, getting a bunch of my own writing edited and reprinted in newspapers from South Carolina to New Mexico, and in online news outlets worldwide. This new project should have an equally vast reach.

I have a new article about halftime at The Agony Booth…

… the halftime of Marvel’s Agent Carter miniseries, that is!

This is the second article I’ve written for The Agony Booth, following “Why Star Trek: The Next Generation’s serialization was just right” back in early January. If you’re interested, you can write something for the ongoing open call for article submissions that led me to contribute both articles!